“The 50th anniversary of the battle of Gettysburg, Union (left) and Confederate (right). Veterans shake hands at a reunion, in Gettysburg, Pennsylvania, 1913.”

My minor was in history, and I admit I’ve never heard of Hannibal Hamlin, the first Republican Vice President. Or perhaps the memory of him was replaced by the cannibal Hannibal in the movie I saw my freshman year, forever cursing the name. I can promise you no one in public school will ever learn his name. But how could we be expected to know the names of the Vice Presidents? We don’t even know what they do. Neither he nor Lincoln look particularly psyched for union preservation in this poster. A former member of both the House of Representatives and the Senate, Hamlin left the pro-slavery Democratic Party in 1856 for the newly-formed Republican Party that aligned with his anti-slavery views. He served only four years, during all but the very last month of the Civil War, and was replaced during the 1864 election by Andrew Johnson. Among other positions that followed, Hamlin returned to the Senate and served two terms, then became the US Ambassador to Spain. Que bueno!

In this picture, I think he bears a passing resemblance to another double H, Howard Hessman, aka Johnny Fever. But that’s just me.

September 1864

General William Tecumseh (arguably the best middle name of all time) Sherman, of the Union Army, has taken Atlanta and orders his men to destroy many of the railroad lines in order to isolate the city from aid.

It’s June 2, 1864. Photographer Tim O’Sullivan has taken to the steeple of Bethesda Church in Virginia to capture this image of Ulysses S. Grant (between the trees), listening to a report by Colonel Bowers (reading at the far right, inside the circle). On Grant’s right is General Horace Porter (reading a newspaper), and on his left is General Rawlins, chief of staff. Here’s a closer look.

In the next image, Grant has risen, walked around the church pews, and is leaning over Meade’s shoulders, consulting a map. Shortly afterward, he will write out orders for the battle of Cold Harbor the next day.

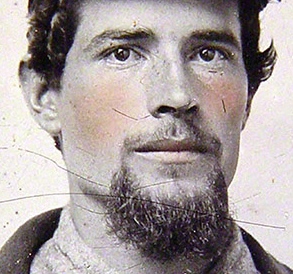

SHORPY: Ca. 1863. “Unidentified soldier in Union uniform with forage cap carrying a bone handle knife in breast pocket.” Sixth-plate tintype, hand-colored. Liljenquist Family Collection of Civil War Photographs, Library of Congress.

Per wikipedia, the Civil War the M1858 forage cap, based on the French kepi, was the most common headgear worn by union troops, even though it was described by one soldier as “Shapeless as a feedbag”. What do you think? Pretty slouchy?

So often, we see pictures of Civil War soldiers, and they look creepy/eerie/stiff, nothing like a man in 2017. But this one is different. Maybe it’s the goatee or the penetrating gaze. He reminds me of someone I’ve seen. Just to put this in perspective, let’s remember that Civil War facial hair often looked more like that of Major General Alpheus Williams.

Not that this beard isn’t AMAZING. Because it is.

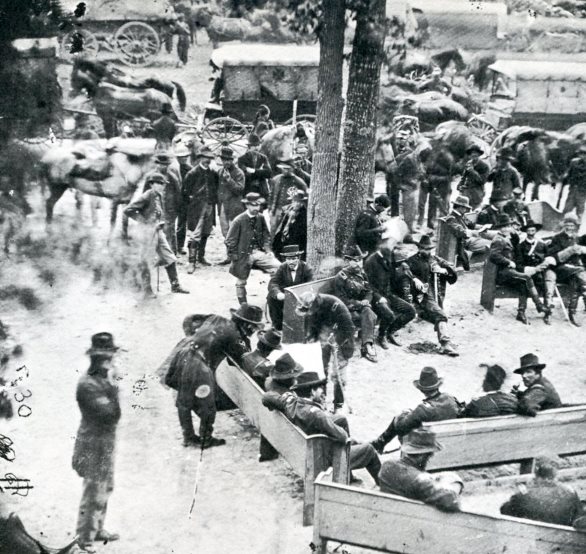

It never ceases to amaze me how low-res and dark a Kodak picture from 1985 can be, and yet this image from a wet plate glass negative by James F. Gibson is clear as a bell. Isn’t it amazing to see this group of fellows at Camp Winfield Scott, near Yorktown, Virginia in May of 1862? It’s from the collection of the Peninsular Campaign, May-August 1862.

This is the full image, but I really enjoy zooming in on the details to get a better understanding of life over 150 years ago.

The sober faces, the wayward hairs, the buttons on their shirts, the metal cup that seems like it would conduct the heat and be hard to handle–so interesting!

In The American Heritage History of American Railroads by Jensen, this 1862 image shows a bridge under construction. Major General George McClellan of the Union Army brought locomotives and cars by ship from Baltimore and ran trains as close to four miles to the Confederate capital. The workmen are seated, and to the left is a photographer’s field darkroom. At that time, photographs had to be developed immediately and while wet.

To their left , a locomotive was arriving on a ship in White House Landing on the Pamunkey River.

Here is another image of the field darkroom, invented by Matthew Brady.

The wagon would carry the chemicals, glass plates, and finished negatives. Can you imagine what would have happened if the horses got startled or took off at a gallop?

I had to break the image in two, so’s you could really take in the amber glow of Old Crow.

I don’t know about y’all, but I love jumping inside Civil War photos. Not that war is fun, but it’s so interesting to see images from when photography was in its infancy, 155 years ago.

By the late 1850s, most American artists had switched from taking mainly portraits made with the daguerreotype process to large glass-plate negatives (allowing them to capture entire scenes) that combined the clarity of the daguerreotype and the endless reproducibility of paper-print photography (metmuseum.org).

And aren’t those two little boys dressed as soldiers just precious? I bet that was a sight for them to see. I wonder if the taller one enlisted, a few years down the road.

If you’re not from the United States, you may not realize that each state celebrates different “Emancipation Days,” depending on which date slaves learned of their freedom. When Abraham Lincoln issued the Emancipation Proclamation on September 22, 1862, it was set to go into effect on January 1, 1863. Obviously, the states that were not yet a part of The Union would have no cause to celebrate. Kansas entered the Union as the 34th state in 1861, but West Virginia did not enter as the 35th state until June of 1863.

This is what The Union flag looked like at that time. Feel free to count the stars!

In Texas, Emancipation Day is celebrated on June 19. It commemorates the announcement of the abolition of slavery made on that day in 1865, when Union General Gordon Granger stood on the balcony of Galveston’s Ashton Villa to read the contents of “General Order No. 3”:

The people of Texas are informed that, in accordance with a proclamation from the Executive of the United States, all slaves are free. This involves an absolute equality of personal rights and rights of property between former masters and slaves, and the connection heretofore existing between them becomes that between employer and hired labor. The freedman are advised to remain quietly at their present homes and work for wages. They are informed that they will not be allowed to collect at military posts and that they will not be supported in idleness either there or elsewhere.

In Texas, that day has been an official state holiday since 1980. We call it Juneteenth, a name coming from a portmanteau of the word June and the suffix, “teenth”, as in “Nineteenth“, coined by 1903. (Thank you, Google.)

Also in 1903, a book was published on U.S. Presidents, which I have in my collection.

Except for a loose binding, it’s in remarkably good shape for a 110-year-old. God willing we should all live to such a ripe old age. I keep it as reference for the next generation, since history is constantly being rewritten by present dictators publishers. As the Academy Award-winning movie Lincoln showed us last year, interest in President Lincoln has not faded. This book paints a loving portrait of the “awful smart chap.” CLICK TO ENLARGE.

As the audience is “young people,” the tone is consistent in its intent, which I find endearing. Here it explains why a tender-hearted Lincoln did not have each deserter shot dead, per accepted war protocol.

“While the world lasts, no one will ever forget the Emancipation Proclamation of Abraham Lincoln.” Let’s hope not.